The Preschool Franchise Flywheel is Alive and Well

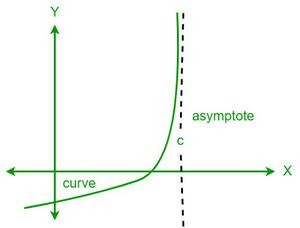

The Franchise Flywheel. The Franchise Machine. The Franchise Rocket Ship. These are terms I often find myself using to describe the point where a cumulative momentum of buzz originating from multiple touchpoints of a kids IP sets in motion a chain reaction which drives awareness and engagement into the proverbial stratosphere. The build is nearly asymptotic (definition here, finally my teenage trigonometry came in handy!) as content, distribution, and product all pull together to deliver the kids media unicorn: a brand on an upward swing ready to capitalize on the moment, ideally for many years to come.

Gabby’s Dollhouse looks to be on the start of this trajectory, something I’ve already written about at length. Two other kids IPs have reached that stratosphere already: CoComelon and Bluey. This is summed up beautifully by the below chart—love it when that happens.

This is fruit born from many years of effort. CoComelon has been at it for well over a decade, although maybe not always so razor targeted on world domination. There have been certain lucky steps for both IPs, which will have helped them along the way.

The History of CoComelon

The CoComelon story dates back to 2006 when a husband-and-wife team set up a YouTube channel to make videos for their kids. This was the heyday of the YouTube bubble and the channel eventually provided enough income to support the family. With this level of success achieved, 2017 saw two key changes that would stimulate the IP from a tidy YouTube business into a full-blown kids content powerhouse. First, there was a pivot to focus on one character, the chubby-cheeked blond-haired baby we all now know as JJ. In addition, the style was adjusted from 2D to 3D. These developments sat the channel on an obscene trajectory. In the following year, 2018, it would go from 238 million to 2 billion monthly views. 2019 would build on this further, bringing the second largest subs gain of the year across the whole of YouTube, up over 110% to 67.4 million.

With that success came notoriety, the machine was engaged, the rocket ship launched. 2020 saw the first announcement of CoComelon consumer products, with master toy partner Jazwares. It would be no surprise that the year would also bring a distribution deal with Netflix and the ultimate acquisition by hot new kids IP stud farm Moonbug Entertainment.

Moonbug is helmed by a number of former Disney executives and was set up with the mission to satisfy the growing appetite for kids content, as new hits from traditional TV networks were suddenly in competition with YouTube native IP. YouTube was (and still is) the biggest kids streamer globally, albeit reluctantly. It has provided fertile ground for these types of shows. What Moonbug could bring to the table with CoComelon was expertise in strategy and revenue streams away from YouTube; namely onward content distribution and consumer products. Other experienced and (helpfully) deep pocketed folks agreed with the potential of this thesis, and Moonbug was acquired in 2021 for a reported $3 billion.

I don’t think even the most seasoned distribution exec could have imagined the impact CoComelon would have when it landed on Netflix in the US. This was the dawn of what some term the “streaming ratings era.” “Trending” rankings were new, and Nielsen were starting to dip their toe in publishing US numbers. CoComelon solidified itself first on the former, followed by the latter. The streak of success the series has seen has defined what engagement can look like when it comes to preschool content on streaming.

The show would also go on to have further distribution globally in places like BBC iPlayer and Warner Media’s linear channel, Cartoonito. With the help of other franchises, including Blippi and Gecko’s Garage, Moonbug has gone onto eye popping % revenue growth year after year.

The History of Bluey

Bluey had a more traditional origin. One might even call it old-fashioned. It was commissioned by a linear broadcaster (yes, they still exist and, more crucially, some still have budgets), the Australian ABC Kids. Fellow Bluey geeks among readers (and I know there are many of you) will be as delighted as I was to find a full academic paper, compiled by Dr Anna Potter, dedicated to the show’s commissioning.

It launched in Australia, on ABC, towards the end of 2018. In what would be a huge boon for the local series, it was acquired for a burgeoning new upstart streaming service you may have heard of, Disney+. Disney’s flagship streamer was to commence staggered launch across markets from the end of 2019. Bluey would be part of the offering, a utility acquired show with excellent brand fit. Different, but high enough quality to supplement their preschool franchises. Before Disney+ launched, something happened which may have been central to the build of the show’s global audience. Interestingly, it was another “traditional” string to the bow of Bluey’s ascent.

Clearly a charming and standout property, Bluey would also come to the attention of Disney’s linear division. Disney Channel and Disney Junior in the US and beyond would pick up the show and, in most cases, start airing the first season before it would appear on Disney+. This points to something that’s bubbled to the top as a central issue in streaming—discoverability. A common concern among streaming-first IP owners (both in kids and beyond) is how to ensure a show is seen.

On linear, there is appointment to view, clear temporal real estate a show inhabits. Some slots are better, some are worse, but you can’t argue that you’re not getting exposure. On streaming, native “rails” and carousels are variously driven by human curation and algorithms. The main visual watch bait is thumbnails, and whilst I fully respect the expertise that goes into a good one, nothing sells video content like video content. The true content sampling that happens when you catch a promo or, even better, channel flick into a show is something that streaming has neither cracked nor equaled.

So Bluey had the best of both. Always-on availability, once Disney+ hit your market, plus daily space in your schedule as it rolled out on Disney’s linear channels. This can only have worked in the IP’s favor, as it continues to do to this day.

The tension with Bluey as a Disney+ flagship show is interesting. Beyond acquisition, the IP isn’t owned or operated by The Walt Disney Company. It was produced by Ludo Studio, with BBC Studios holding global and merchandising rights. This renders Bluey a direct competitor franchise to preschool IPs like Mickey Mouse and Winnie the Pooh. Potentially dialing up the #awks factor even further, a back-end percentage on consumer product revenues from Bluey to Disney would be pretty typical in this type of deal. Instead of my usual charts, I’ve summed this up in the below image:

This isn’t such strange ground to Disney as it might sound. Channel teams have a track record in picking up rights to strong third-party programming they can use to serve their platforms, without the pressure of satisfying internal stakeholders and business groups. PJ Masks and Miraculous: Tales of Ladybug & Cat Noirhave been through a similar pipeline. There’s an argument to say that, in certain cases, this is beneficial to the third-party IP, as content teams can decide on roll-outs based purely on what’s going to drive performance, instead of being constrained by internal Disney needs, like Consumer Products or Parks launch timelines.

Bluey would start rolling out consumer products, with Australia as a perfect test bed, in 2019. A global launch would confidently follow that success in Christmas 2020.

In that first full year of global consumer product roll out, the brand’s master toy licensee, Moose Toys, saw revenues surge. The Australian company forecast uplift of 25% to AUD $800M in 2020/2021, and let’s not forget that’s in the middle of a pandemic when physical retail was severely curtailed. From then on, ratings, engagement, and revenue all started to build. Last fall, Thanksgiving 2022 would see a decisive statement: peak marketing dollars spent on a float at the Macy’s Thanksgiving Parade.

Where Are We Now?

So there’s a bit of background on the rise of CoComelon and Bluey. Not as many details as for Gabby’s Dollhouse, but it’s always hard to pan for these after the fact (and do drop me a line if there’s anything I’ve missed). Two very different journeys to be sure, one very much new guard, one with a distinct whiff of the old.

Streaming

That brings us to now. CoComelon is at year two or three of being a global powerhouse IP, having been in track for six years. Bluey is following a year or two behind. In terms of US streaming ratings, the past few months have seen the properties go neck and neck. Bear in mind that Bluey is pulling these numbers off Disney+ with household penetration of around 31%; CoComelon on Netflix is a good league higher, at ~51%. It will be interesting to see how Bluey season 3 impacts. It dropped on July 12th, so we'll know when Nielsen publish their rankings at around a month’s delay.

YouTube

CoComelon still slaughters on its home turf of YouTube, of course. An illustrious member of The Billion Club, a small number of channels which pull in billions of views per month. Last I looked, CoComelon was the only animated kids property doing this, rubbing shoulders with kidfluencers Kids Diana Show, Like Nastya, and Vlad and Niki.

Bluey is very much in growth on YouTube, doing well, now seeing close to 150 million views monthly. Good, but a drop in the CoComelon ocean. Like in Nielsen Streaming Content Ratings, there is some visible downturn of CoComelon’s YouTube views, but together these are probably best characterized as a stabilization, rather than a softening. On a bad day, the property is still absolute gangbusters in terms of content engagement.

Consumer Products

On the toy front, US NPD data I saw from 2022 tells a noteworthy story. Despite being the newer kid on the block, Bluey business is listed as more than double that of CoComelon. Recent year-end results from BBC Studios cited the property as directly driving 10% growth in the consumer products division as a whole. They seem to be calling the right tune on toy design x content distribution x consumer sentiment. And there’s no denying that one thing Bluey has over CoComelon is outstanding sentiment among wallet holders, er… I mean parents.

In Conclusion...

There’s no single perfect external metric that denotes franchise success. Indeed, the real cut of the chaff will be fully internal, when marketing dollars net off against retail sales that net off against royalties that net off against operational overheads that net off against... you get the idea! CoComelon has been dominant in recent years, of that there is no doubt. Based on what we can see from the data, Bluey is coming up close behind though. Again I’ve used an image as opposed to a chart to sum this up:

The bottom line is that both properties are very much on their own unique franchise rocket ships. What lies ahead has its own difficult bits too… Sustain. With a name that thrilling, you can only imagine audiences clamoring with anticipation! Joking aside, the art of sustain is tricky. How do you reinvigorate an IP year in year out? Content, activations, and marketing all need to bring something fresh and exciting. This can be easier with IP like Paw Patrol, where themes like Sea Rescue, Sky Rescue, and Space Rescue (have they done that one yet?) are easy to fit in. This type of reskin doesn’t sit as comfortably for family-based shows like Bluey and CoComelon.

At least they both approach this from a platform of success. The franchises are cemented in the history books of kids IP legend. They prove that the preschool franchise may be evolving, but it’s still alive and well, and ripe for the occasional unicorn.